Post contents

In JavaScript, you're able to use a class as a template for your objects:

class Car { wheels = 4; honk() { console.log("Beep beep!"); }}// `fordCar` is an "instance" of Carconst fordCar = new Car();console.log(fordCar.wheels); // 4fordCar.honk();As shown above, a class can have a collection of properties and methods. In addition to stateless methods, you can also reference the class instance and store state within the class object itself:

class Car { // Gallons gasTank = 12; // Default MPG to 30 constructor(mpg = 30) { this.mpg = mpg; } drive(miles = 1) { // Subtract from gas tank this.gasTank -= miles / this.mpg; }}const fordCar = new Car(20);console.log(fordCar.gasTank); // 12fordCar.drive(30);console.log(fordCar.gasTank); // 10.5The this keyword here allows us to mutate the class' instance and store values. However, the usage of this can be dangerous and introduce bugs in unexpected ways, depending on context.

Let's take a look at:

- When

thisdoesn't work as expected - How we can fix

thiswithbind - How to solve issues with

thiswithout usingbind

When does this not work as expected?

Take the following two classes:

class Cup { contents = "water"; consume() { console.log("You drink the ", this.contents, ". Hydrating!"); }}class Bowl { contents = "chili"; consume() { console.log("You eat the ", this.contents, ". Spicy!"); }}cup = new Cup();bowl = new Bowl();If we run:

cup.consume();It will console.log "You drink the water. Hydrating!". Meanwhile, if you run:

bowl.consume();It will console.log "You eat the chili. Spicy!".

Makes sense, right?

Now, what do you think will happen if I do the following?

cup = new Cup();bowl = new Bowl();cup.consume = bowl.consume;cup.consume();While you might think that it would log "You eat the chili. Spicy!", it doesn't! Instead, it logs: "You eat the water. Spicy!".

Why?

The this keyword isn't bound to the Bowl class, like you might otherwise expect. Instead, the this keyword searches for the scope of the caller.

To explain this better using plain English, this might be reiterated as: "JavaScript looks at the class that uses the

thiskeyword, not the class that creates thethiskeyword"

Because of this:

cup = new Cup();bowl = new Bowl();// This is assigning the `bowl.consume` messagecup.consume = bowl.consume;// But using the `cup.contents` `this` scopingcup.consume();

Fix this usage with bind

If we want bowl.consume to always reference the this scope of bowl, then we can use .bind to force bowl.consume to use the same this method.

cup = new Cup();bowl = new Bowl();// This is assigning the `bowl.consume` message and binding the `this` context to `bowl`cup.consume = bowl.consume.bind(bowl);// Because of this, we will now see the output "You eat the chili. Spicy!" againcup.consume();

While bind's functionality follows its namesake, it's not the only way to set the this value on a method. You're also able to use call to simultaneously call a function and bind the this value for a single call:

cup = new Cup();bowl = new Bowl();cup.consume = bowl.consume;// "You drink eat the water. Spicy!"cup.consume();// "You eat the chili. Spicy!"cup.consume.call(bowl);JavaScript's .call method works like the following:

call(thisArg, ...args)Such that you're not only able to call a function with the this value, but also pass through the arguments of the function as well:

fn.call(thisArg, arg1, arg2, arg3)Can we solve this without .bind?

The

.bindcode looks obtuse and increases the amount of boilerplate in our code. Is there any other way to solve thethisissue withoutbind?

Yes! Introducing: Arrow functions.

When learning JavaScript, you may have come across an alternative way of creating functions. Sure, there's the original function keyword:

function SayHi() { console.log("Hi");}But if you wanted to remove a few characters, you could alternatively use an "arrow function" syntax instead:

const SayHi = () => { console.log("Hi");}Some people even start explanations by saying that there are no differences between these two methods, but that's not quite right.

Take our Cup and Bowl example from earlier:

class Cup { contents = "water"; consume() { console.log("You drink the ", this.contents, ". Hydrating!"); }}class Bowl { contents = "chili"; consume() { console.log("You eat the ", this.contents, ". Spicy!"); }}cup = new Cup();bowl = new Bowl();cup.consume = bowl.consume;cup.consume();We already know that this example will log "You eat the water. Spicy!" when cup.consume() is called.

But what happens if we instead change Bowl.consume() from a class method to an arrow function:

class Cup { contents = "water"; consume = () => { console.log("You drink the ", this.contents, ". Hydrating!"); }}class Bowl { contents = "chili"; consume = () => { console.log("You eat the ", this.contents, ". Spicy!"); }}cup = new Cup();bowl = new Bowl();cup.consume = bowl.consume;// What will this output?cup.consume();While it might seem obvious what the output would be, if you thought it was the same "You eat the water. Spicy!" as before, you're in for a suprise.

Instead, it outputs: "You eat the chili. Spicy!", as if it were bound to bowl.

Why does an arrow function act like it's bound?

That's the semantic meaning of an arrow function! While function (and methods) both implicitly bind this to a callee of the function, an arrow function is bound to the original this scope and cannot be modified.

Even if we try to use .bind on an arrow function to overwrite this behavior, it will never change its scope away from bowl.

cup = new Cup();bowl = new Bowl();// The `bind` does not work on arrow functionscup.consume = bowl.consume.bind(cup);// This will still output as if we ran `bowl.consume()`.cup.consume();Problems with this usage in event listeners

Let's build out a basic counter button that shows a button with a number inside. When the user clicks the button, it should increment the number inside of the button's text:

// This code doesn't work, we'll explore why soonclass MainButtonElement { count = 0; constructor(parent) { this.el = document.createElement('button'); this.updateText(); this.addCountListeners(); parent.append(this.el); } updateText() { this.el.innerText = `Add: ${this.count}` } add() { this.count++; this.updateText(); } addCountListeners() { this.el.addEventListener('click', this.add); } destroy() { this.el.remove(); this.el.removeEventListener('click', this.add); }}Let's see if this button works by attaching it to the document's <body> tag:

new MainButtonElement(document.body);It renders!

However, if we try to click the button, we get the following error:

Uncaught TypeError: this.updateText is not a function

Why is this?

We might get a hint if we add a console.log(this) inside of our add() method:

add() { console.log(this); // ...}

<button>Add: 0</button>

It seems like this is being bound to the button HTMLElement instance! 😱

How did this happen?

Well, remember that this is being bound to something. In this case, it's being bound through the addEventListener to the instance of the element in JavaScript.

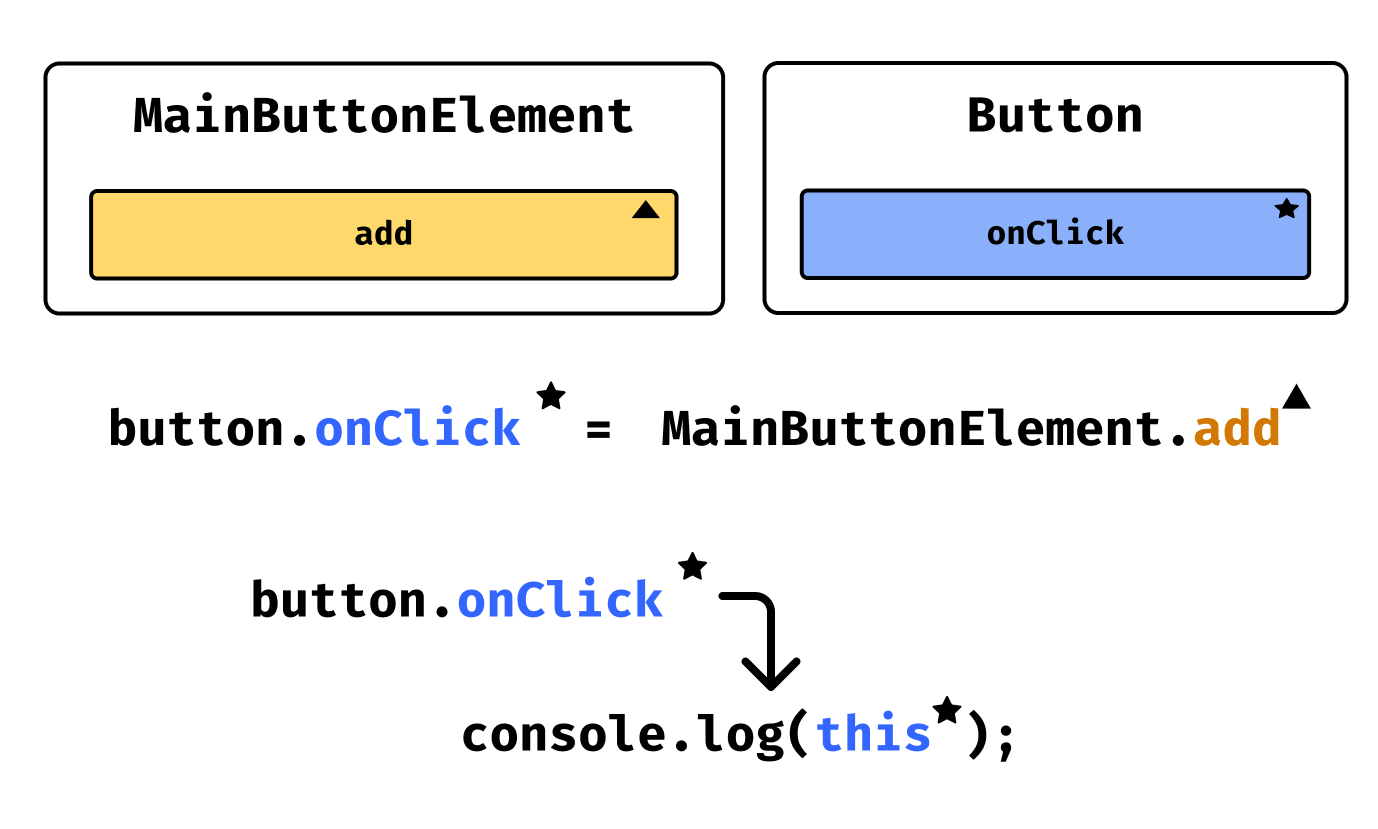

We can then think of your browser calling an event on button to look something like this:

/** * This is a representation of what your browser is doing when you click the button. * This is NOT how it really works, just an explanatory representation */class HTMLElement { constructor(elementType) { this.type = elementType; } addEventListener(name, fn) { for (let event of this.events) { fn(event) } }}document.createElement("button");Let's chart out what's happening behind-the-scenes:

Fixing this event listener usage

To fix the issues with this usage in event listeners, we can reuse our existing knowledge from earlier and do one of two things:

.bindthe usage of.addin the event listener:

// This code doesn't work eitherclass MainButtonElement { count = 0; constructor(parent) { this.el = document.createElement('button'); this.updateText(); this.addCountListeners(); parent.append(this.el); } updateText() { this.el.innerText = `Add: ${this.count}` } add() { this.count++; this.updateText(); } addCountListeners() { this.el.addEventListener('click', this.add.bind(this)); } destroy() { this.el.remove(); // This won't remove the listener properly this.el.removeEventListener('click', this.add.bind(this)); }}However, this has some problems, as two .bind functions are not referentially stable:

function test() {}console.log(test.bind(this) === test.bind(this)); // FalseWhich is required for removeEventListener usage to remove the event listener properly. This means that we instead have to bind add at the function's base:

class MainButtonElement { count = 0; constructor(parent) { this.el = document.createElement('button'); this.updateText(); this.addCountListeners(); parent.append(this.el); } updateText() { this.el.innerText = `Add: ${this.count}` } // 😖 add = (function() { this.count++; this.updateText(); }).bind(this) addCountListeners() { this.el.addEventListener('click', this.add); } destroy() { this.el.remove(); this.el.removeEventListener('click', this.add); }}Alternatively, we can...

- Use an arrow function rather than a class method:

class MainButtonElement { count = 0; constructor(parent) { this.el = document.createElement('button'); this.updateText(); this.addCountListeners(); parent.append(this.el); } updateText() { this.el.innerText = `Add: ${this.count}` } add = () => { this.count++; this.updateText(); } addCountListeners() { this.el.addEventListener('click', this.add); } destroy() { this.el.remove(); this.el.removeEventListener('click', this.add); }}Wrapping it up

Using the this keyword is nearly unavoidable when using class-based JavaScript. It enables you to mutate state within the class to reference for later usage.

While some JavaScript is able to avoid this, it's particularly helpful to know when using frameworks such as Angular which uses classes as the primary means for defining a component.

Speaking of - want to learn how to use Angular? I'm writing a free book series called "The Framework Field Guide" that teaches React, Angular, and Vue all at once. Click the link to learn more about the book and be notified when it launches!

Happy hacking!